Horses: Small Strongyle Life Cycle

Life Cycle of the Small Strongyles (cyathostomins)

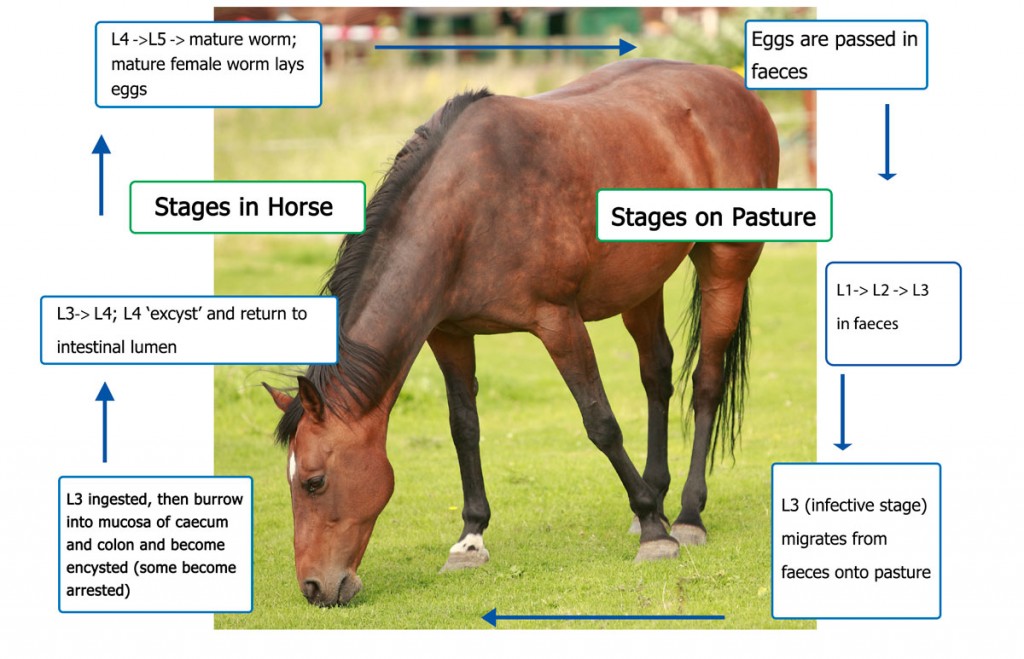

Adult female small strongyles live in the lumen of the large intestine of the horse. They shed eggs which are found in the horse’s faeces. The eggs hatch and develop sequentially into various larval stages (L1, L2, etc). Development of L1 to L3 occurs in the faeces, then the L3 (the only stage capable of infecting a horse) migrate from the faeces onto the pasture and are ingested by the horse. Egg survival and hatching, and larval survival and development depend on climatic conditions (temperature and moisture). Dry conditions kill eggs and larvae. Larvae, but not eggs, will tolerate freezing. Temperatures below about 7°C do not support hatching or larval development. With adequate moisture, the rate of larval development increases proportionally with temperature up to about 30°C.

Eggs and larvae can survive for considerable periods in cool weather with adequate moisture, but survival of larvae is reduced at warmer temperatures due to rapid depletion of limited energy reserves (with adequate moisture, the optimum temperature for survival is about 15°C, while above 30°C, larvae will die). Larvae can survive for 12 months on pasture under favourable conditions, but generally survive < 3 months in summer and < 6 months in winter. In winter rainfall areas in Australia, larval populations will be high in autumn, winter and spring, while in summer rainfall areas, larval populations will be high in spring, summer and autumn.

When L3 are consumed by the horse, they burrow into the mucosal tissue of the caecum and colon and become encysted (the cyst wall protects them from most drugs). These larvae either develop (within the cysts) into L4 or become arrested (development stops).

L4 ‘excyst’ (exit the cysts) and return to the lumen of the large intestine where they develop into L5 and then into mature worms which complete the life cycle with the females producing eggs. Arrested larvae remain encysted for varying periods of time before emerging from the cysts. Often the period of encystment is long (up to a year or more). Emergence of large numbers of arrested larvae, often in late winter/early spring in cooler climates, causes larval cyathostomosis, a clinical disease associated with intestinal mucosal damage, which can be fatal. Encysted larvae are usually present in much greater numbers than the adults in the intestinal lumen. The length of the life cycle varies from about 6 weeks to 2.5 years, depending on the amount of time that the larvae remain arrested.